Colombian scientists contribute to control of one of the most powerful bacteria in hospitals

By: Marisol Ortega Guerrero

Photos:

Health and Wellness

By: Marisol Ortega Guerrero

Photos:

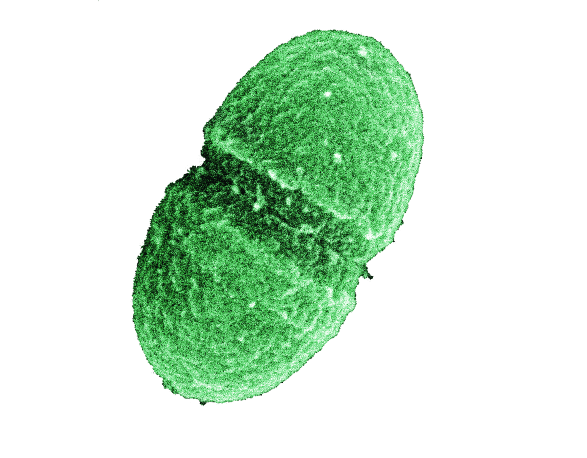

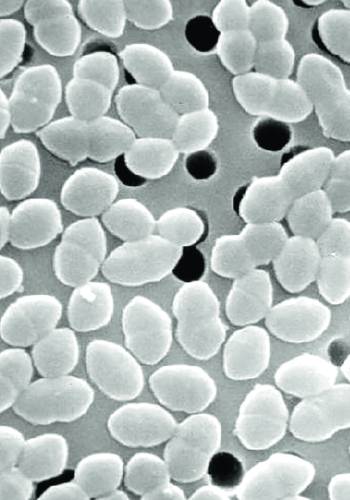

Because of the current situation, the world is only talking about coronavirus; however, there are other microorganisms that are also quite harmful to human health and are equally challenging for science. This is the case of the bacteria Enterococcus faecium (VREfm), classified as one of the 10 pathogens or microorganisms more related to infections associated with medical care; even some research groups consider it a “superpathogen,” because it is highly resistant to antibiotics, particularly to vancomycin.

"It is a great colonizer that causes disease when the host has an imbalance. It can cause infections in the bloodstream, the urinary system, the soft tissue, the Central Nervous System, and the pelvis,” explains Dr. Giovanni Antonio Rodríguez Leguizamón, head of research of the Hospital Méderi, and professor, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario.

In other words, upon entering the human body, the bacteria can replicate (produce multiple copies of itself) and spread through organs and bloodstream to continue its replication indefinitely, depending on the health condition that the person has.

Dr. Rodríguez is part of a group of Colombian scientists who have studied this bacteria to expand existing knowledge as it is relevant to know more about its characteristics because of its relationship with infections in hospitals. The research study, which is supported by the Universidad del Rosario, was published in 2019 in the specialized journal BMC Infectious Diseases, indexed internationally with a very favorable impact factor in the scientific world.

There, the highlighting of this work as one revealing a pathogen of “high priority for research and development of new antibiotics in the world” has allowed to not only stop outbreaks of infection but also improve the environment and reinforce very efficient control measures. The main one is handwashing in the hospital environment, a transcendental issue, considering the bacteria’s high resistance to almost all therapy options available.

How the study was performed

“We decided to address the management of an infection outbreak that was presented in a hospital in Bogotá from a different point of view from what would normally have been done, including molecular and clinical components. It was a very good opportunity to start a partnership work with the Fundación Instituto de Inmunología de Colombia, Fidic (Foundation of Colombia's Inmunology Institute), which has all the molecular support to carry out this type of study,” explains Dr. Rodríguez.

Adopting the approach of molecular biology, it was possible to know how the infection transited; when it was present, in which sector, and on what days; and how the transmission chain was.

For Dr. Manuel Alfonso Patarroyo, head, Department of Molecular Biology and Immunology, Fidic, and professor, School of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universidad del Rosario, it was very important to know which variant of the pathogen produced the infection of new people. “Even if they belong to the same species, in this case Enterococcus faecium, small variations may be found between clinical isolates from different patients, so if we can analyze in detail the molecular composition of each isolate, this allows us to know the chain of transmission, that is, who transmitted the bacteria to whom,” he explains.

Therefore, a total of 33 isolates of non-duplicated VREfm were recovered during a 5-month period (May 2016 to September 2016) from 29 hospitalized patients (three of them acquired it outside the healthcare setting) and another four from environmental surfaces (bed rails and infusion pump, among others). All were analyzed using clinical samples and other alternatives.

Using microbiological techniques, researchers were able to determine that the focus of infection in the hospital was found to be an Enterococcus faecium resistant to vancomycin. With molecular techniques, they characterized clonality, (evaluation to check whether the bacteria are the same or different) so that it was possible to know, for example, what kind of variant one person had and whether it was identical to the others.

“We found a very important transmission pattern through the hands of caregivers or health workers, which reinforced all the construction around infection control, from such a simple measure, that, nowadays, is also highly promoted, such as handwashing,” adds Dr. Patarroyo.

The authors reiterate in their article precisely that “the prevention of these types of hospital threats could depend on reinforcing one of the oldest and most profitable epidemiological interventions: Handwashing.”

Multidisciplinary research was also essential in order to identify the impact of other key variables on the presence of outbreaks, such as those related to the rational use of antibiotics and terminal disinfection. Although they already had consolidated programs in the hospital in this regard, they had to be strengthened and expanded, particularly after noting that this pathogen can survive on a surface up to 5–6 years. Scientists have determined that it is very resistant and withstands very low and very high temperatures, easily becoming a reservoir of continuous infection.

Bacteria Enterococcus faecium (VREfm) is classified as one of the 10 pathogens or microorganisms more related to infections associated with medical care.

"The contribution made by the study is interesting and valuable to address infections associated with healthcare, because it is more precise. It helps decision-makers, in some sense, by giving them more information about how to channel technical resources for infection control,” explains Dr. Rodríguez.

Teamwork

For more than a year of work, the research team followed up on 16 cases and analyzed the results. Besides the Doctors Patarroyo and Rodríguez from the School of Medicine and Health Sciences of the Universidad del Rosario, other persons were part of it: Dr. Juan Mauricio Pardo, scientific director, Méderi, and Professor at the Universidad del Rosario; Nancy Carolina Corredor, doctor, Hospital Universitario Mayor Méderi ; Carolina López, bacteriologist, Fundación Instituto de Inmunología de Colombia , and doctorate student, Universidad del Rosario; Lina Prieto and Paula Aguilera, epidemiologists, Méderi; Aura Lucía Leal, microbiologist, Universidad Nacional; Maria Victoria Ovalle, microbiologist, Instituto Nacional de Salud (INS); and Claudia Chica, bacteriologist, Compensar.

The research could not have had a better response than the international publication with the article An epidemiological and molecular study on the spread of Enterococcus faecium, resistant to vancomycin in a university hospital in Bogotá, Colombia, published last year, for which the researchers affirm that they are more than happy with this result with regard to their contributions from a scientific, health, and preventive point of view..

“Another very important point is that as professors, and in my particular case as a professor from the area of epidemiology in public health, where I deal with the issue of infections and epidemiological surveillance, it is very satisfactory to show students a result of what I am teaching in class. We can see that there are molecular tools highly useful for a clinical epidemiological approach, that it really exists, and that it can be done in Colombia. That is to say, one of the satisfactions is the transfer of knowledge, and being able to do it in a high-quality journal validates that the strategy is novel and can be replicated. It is a different approach, very valuable to face this problem,” says Dr. Rodríguez.

ANow, the researchers have another project with pathogens, supported by their ability to work as a team and their friendship, aimed at making more contributions to science and medicine. The following is none other than one that has been kept in suspense: Candida spp and “its cousins.” “A yeast that is fascinating from the point of view of infection associated with healthcare. Fungi sometimes are not on the radar, but when they arrive and cause problems, these are serious,” says Dr. Rodríguez.

The basics of Enterococcus faecium

Bacteria are microorganisms grouped in large families that can be identified, first, according to an alcohol-based stain: If they retain ink, they are gram-positive; if not, they are gram-negative. Second, they can be differentiated by their shape: Cocci, if rounded, and bacilli, if they are elongated.

It should be noted that today there are more advanced methods of molecular biology-based identification and that this is precisely one of the topics described in the article published. Specifically, Enterococcus faecium is a gram-positive bacteria with rounded shape, described since 1886, found predominantly in the gastrointestinal systems of different animals but also on the skin and in other parts of the body.

It can produce “pelvic infections, infections in the bloodstream, in the urinary tract, in the soft tissue, and the Central Nervous System, as well as endocarditis, among others,” says Doctor Giovanni Antonio Rodríguez.

For his part, Dr. Manuel Alfonso Patarroyo recalls that this bacteria is considered by some research groups as a “superpathogen,” “first, because it can be found colonizing different areas. Second, because it lives a long time on inanimate objects, it can last there for years, and third, because it easily acquires properties of resistance to antibiotics from other pathogens.”

It is a reality that E. faecium (VREfm) is resistant to vancomycin, which came to be known for the first time in Europe and the United States at the end of the 1980s. This seems to have appeared, among other reasons, as a consequence of undue use of avoparcin (growth promoter) in livestock and poultry, in addition to the excessive use of antibiotics in hospital environments, despite the fact that it can also occur outside them.